Canada Doesn’t Need You

To not know the many stories of exclusion that continue to this day is to ensure we walk blind into the next bout of fear mongering or race-based panic.

Lyrics

CANADA DOESN’T NEED YOU (words and music Mike Ford 2007)

Race in the night to the dock to escape

From the boots to the boat quietly to the sea

Look for a port for a shore to alight

To arrive happy day but the eyes turn away

Crowd in the hold of the boat off the shore

Turn away refugee while the wind blows to say

Canada doesn’t need you

Canada doesn’t need you, no

Ice on the tarp of the stall public yard

Doing time ‘til the train all the eyes look away

Torn from the coast out of homes, fishing boats

To the shack evacuate, isolate, lock away

Sour sugar beet, no strawberries today

And tomorrow again will the wind blow to say

Canada doesn’t need you

Canada doesn’t need you, no, doesn’t need you

No, doesn’t need you

Footsteps ignore, step around on the ground

City street not the snow where you hunted and played

Torn from the north shorn of hair and of home

And of tongue not allowed in the land it was made

Oh what would it take not to hear ‘go away’

Would it help to be white, Cheerio as they say

Canada doesn’t need you

Canada doesn’t need you no, won’t receive you no, don’t believe you no

Doesn’t need you

Key Terms & Phrases

Ice on the tarp, public yard

In January 1942, as a first step in the order to relocate all Canadians and immigrants of Japanese ethnicity, Vancouver’s Hastings Park was converted into a ‘holding station’ for evacuees. Without any concessions to privacy or sanitary conditions, thousands of Japanese Canadians were packed like cattle into unheated makeshift tents and stables, waiting for their turn to be shipped by train to waiting deplorable conditions of ‘ghost-towns’ in the BC interior.

Sour sugar beets, no strawberries today

Thousands of the interned Japanese Canadians were taken away from successful and hard-earned fishing boat businesses (all boats and possessions were confiscated and sold off by the government, ostensibly to pay for relocation expenses. Other evacuees had spent decades building up strawberry farms and canneries, only to be robbed of them upon internment. Thousands of the interned were sent to forced labour camps during the war – many of these being Sugar Beet farms in Alberta.

Shorn of hair, and of home, and of tongue, not allowed

As part of official government policy through the 19th and much of the 20th Century, thousands of young First Nations boys and girls were forcibly removed from their families and kept in church-run residential schools, often hundreds or thousands of miles from their homes. Often, the first step upon arrival involved having their heads shaved. In almost all residential schools, even a single word spoken of one’s indigenous language resulted in harsh treatment and beatings.

Historical Context

Jewish refugees leading up to WW2

Between 1933 and 1939, millions of Jews attempted to escape Hitler’s Germany. Many of them reached neighbouring European countries, often being caught shortly after as those countries in turn fell under Nazi control. Hundreds of thousands fled across the ocean. The United States accepted over 240,000 of these refugees leading up to WW2. Canada accepted only 4,000, before adhering to a de facto official policy that decreed that, as regarded further Jewish refugees ‘none is too many’. The most illustrative example of Canada’s actions at the time are perhaps seen in what is referred to as “The St Louis Incident”. A story later told in many books and in the film “The Voyage of the Damned”, The St. Louis Incident refers to the plight of 907 passengers on the ocean liner ‘St. Louis”, which arrived off Canada’s east coast in June of 1939. The passengers were Jewish refugees from Germany, who had to pay exorbitant prices to board the ship, were allowed to bring the equivalent of only 5 dollars with them, and were among the last to be allowed to leave the country legally. They had expected to land in Cuba, but during their crossing the government and ‘climate’ had changed there (it is reported that Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels sent aids to work up anti-Jewish sentiment in Havana). They were forced to wait off shore, and were soon told that their visa permits were nullified. The ship then sailed to Florida and up the U.S. coast, where their requests to land were officially denied. When they tried to land in Canada, they were once again denied – the official government line was that they “would not make good settlers”. They then had no choice but to return to Europe, making their war variously to England, the Netherlands, France and elsewhere. As many of those countries were soon occupied by the Nazis, most of those who made it to the continent were subsequently taken to concentration camps and died therein. The incident is a horrible black mark on Canada’s record – not only for the racist exclusionary policy, and what that meant for the refugees, but also because Goebbels was able to use the actions of the North American nations to support his claim that no one wanted the Jews and that they were indeed undeserving. It has been claimed (dubiously) that Canadian officials couldn’t possible have known what the Jewish refugees were fleeing. Whatever the case, it remains that this vast, under-populated and materially rich country complacently deemed entire races, no matter what their plight, unworthy of landing and living here.

Internment of Japanese Canadians during WW2 (verse two)

The following is a time-line of events relating to the wartime internment.

1895 - Government of B.C. denies franchise (vote) to citizens of Asian descent.

1904 - Japanese Canadian farmers begin to settle in the Fraser Valley and establish themselves as successful berry farmers.

1906 - The first Japanese language school is established in Vancouver.

1907 - Anti-Asian riot in Vancouver.

1914 - Outbreak of World War I. 200 British Columbia Issei (1st Generation Japanese immigrants) enlist.

1919 - BC reduces the number of fishing licenses to "other than white residents".

1921 - Asiatic Exclusion League is formed.

1931 - Remaining WWI veterans finally receive the right to vote and become the only Japanese Canadians to be enfranchised.

1938-40 RCMP kept surveillance on the Japanese community. However, they recorded no subversive activity.

1939 - Canada declares war with Germany.

World War II and the War Measures Act

1941 - Compulsory registration of all Japanese Canadians over 16 years is carried out by the RCMP.

Dec. 7 - Japan attacks Pearl Harbor. Canada declares war on Japan.

Dec. 8 - 1,200 fishing boats are impounded and put under the control of the Japanese Fishing Vessel Disposal Committee. Japanese language newspapers and schools closed. Insurance policies are cancelled.

Dec. 16 - Mandatory registration of all persons of Japanese origin, regardless of citizenship, with Registrar of Enemy Aliens.

Feb.7 - All male "enemy aliens" between the ages of 18-45 are forced to leave the protected coastal area before April 1. Most are sent to work on road camps in the Rockies. Some are sent to Angler, ON.

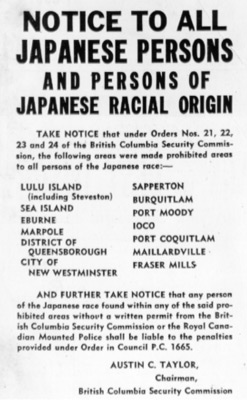

Feb. 26 - Notice is issued by the Minister of Justice ordering all persons of "the Japanese race" to leave the coast. Cars, cameras and radios confiscated. Dusk-to-dawn curfew is imposed. Property and belongings are entrusted to the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property as a "protective measure only".

Mar. 16 - First arrival at Vancouver's Hastings Park holding center. All Japanese Canadian mail is censored from this date.

Mar. 25 - B.C. Security Commission initiates a program of assigning men to road camps and women and children to ghost town detention camps.

June 29 - The Director of Soldier Settlement is given authority to purchase or lease farms owned by Japanese Canadians. He subsequently buys 572 farms without consulting the owners.

Oct - 22,000 persons of whom 75% are Canadian citizens (60% Canadian born, 15% naturalized) have been uprooted forcibly from the coast.

1943 - Order in Council grants the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property the right to dispose of Japanese Canadian properties in his care without the owners' consent.

1944 - Aug. 4 Prime Minister King states it is desirable that Japanese Canadians are dispersed across Canada. Applications for "voluntary repatriation" to Japan are sought by the Canadian government. Those who do not must move east of the Rockies to prove their loyalty to Canada. "Repatriation" for many means exile to a country they have never seen before.

The Post-World War II Years

1946 - Jan. 1 On expiry of the War Measures Act, the National Emergency Transitional Powers Act is used to keep the measures against Japanese Canadians in place.

May 31 - Boats begin carrying 4000 exiled Japanese Canadians to Japan.

1949 - Mar. 31 Restrictions imposed under the War Measures Act are lifted and franchise is given to Japanese Canadians.

1967 - Canadian government announces a point system for new immigrants. "Race" is no longer a criterion for immigration.

Oct. 1987 - Founding of the National Coalition for Japanese Canadian Redress. The Coalition consists of a broad cross-section of individuals, ethnic organizations, unions, professional associations and cultural groups. Rally on Parliament Hill, Ottawa by supporters of Redress.

1988 - Sept. 22 Acknowledgement, apology and compensation.

Canada’s Residential School System (verse three) From the 19th Century to 1996, over 130 ‘Residential Schools’ were operated across Canada. Over150,000 aboriginal, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools. The schools were established with the assumption that native children could be successful if they assimilated into mainstream Canadian society by adopting Christianity and speaking English or French. One government official noted that the desired intent was to “kill the Indian in the child”.

Students were discouraged from speaking their first language or practicing native traditions. If they were caught, they would experience severe punishment. Throughout the years, students lived in substandard conditions and endured physical and emotional and sexual abuse. They were in school 10 months a year, away from their parents. All correspondence from the children was written in English, which many parents couldn't read. Brothers and sisters at the same school rarely saw each other, as all activities were segregated by gender.

When students returned to the reserve, they often found they didn't belong. They didn't have the skills to help their parents, and became ashamed of their native heritage. The skills taught at the schools were generally substandard; many found it hard to function in an urban setting. The aims of assimilation meant devastation for those who were subjected to years of mistreatment.

In 1990, Phil Fontaine, then leader of the Association of Manitoba Chiefs, called for the churches involved to acknowledge the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse endured by students at the schools. A year later, the government convened a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Over the years, the government worked with the Anglican, Catholic, United and Presbyterian churches, which ran residential schools, to design a plan to compensate the former students. In 2007, two years after it was first announced, the federal government formalized a $1.9-billion compensation package for those who were forced to attend residential schools, portions of which have since been paid to some survivors of the Residential School system.

Official Apology

On June 11, 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, made a Statement of Apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools, on behalf of the Government of Canada. Although susceptible to the complaint that such a statement is only words, and lacking in substance, Native leaders have avowed to the significance of the event, as an official and important step towards healing on all sides.

Truth & Reconciliation Commission

First Nations, Inuit and Métis former Indian Residential School students, their families, communities, the Churches, former school employees, Government and other Canadians are presently (2011) participating in a Truth & Reconciliation Commission. The Commission’s mandate is to document the truth of survivors, families, communities and anyone personally affected by the Indian Residential School experience, to inform all Canadians about what happened in Indian Residential Schools to guide and inspire Aboriginal peoples and Canadians in a process of reconciliation and renewed relationships that are based on mutual understanding and respect. It is seen by its founding partners as a “profound commitment to establishing new relationships embedded in mutual recognition and respect that will forge a brighter future. The truth of our common experiences will help set our spirits free and pave the way to reconciliation.”

Composer's Notes

I suppose the study of any country’s history will yield feelings of surprise, pride, celebration, anger, frustration and shame, in varying degrees – and Canada, of course, is no exception. While researching the title track for a previous album – Canada Needs You, volume one, I found myself discovering a fact that should have been obvious – namely, that the glorious Open Door Policy circa 1900 Canada offered free land to immigrants, so long as they were Caucasian, in effect. And of course immigrants from some countries were not only not offered free land, but had further official hurdles to contend with (a fortune in head tax for Chinese, for instance).

I had originally set out to write a song that focused only on what inspires this song’s second verse, but after reading three specific books in succession, I realized I wanted to include several thematically-linked topics in one. That linking theme is exclusion – more precisely racially-based exclusion, and the further hardships it fosters.

The names of the 3 books follow. I believe they should be mandatory reading for every Canadian. Period.

None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948 Irving Abella & Harold Troper - Dennys, Toronto, 1982. The result of extensive research, it tells the story of how the Canadian government did everything in its power to bar the door to European Jews trying to flee Nazi persecution, and how Canada did less than all other Western countries to help the Jews despite mounting reports of Adolf Hitler's genocide.

The Enemy That Never Was - a History of the Japanese Canadians Ken Adachi - McClelland & Stewart, Toronto 1976. A ground breaking historical work. Although covering many facets of a diverse and century-long experience in Canada, the book focuses tellingly on the shameful treatment of Japanese Canadians leading up to, during, and after WW2. The internment, loss of civil rights, property, businesses, the damage to families, the blotting out of opportunity, was entirely racist and frighteningly vindictive. It had precious little to do with wartime security (RCMP and Army Brass alike voiced their belief in how unnecessary it was, no Japanese Canadian was ever found guilty of any seditious action or intent) and practically everything to do with ignorant racist paranoia, fear mongering and scape-goating on Canada’s west coast and in the corridors of power.

The Kiss of the Fur Queen Tomson Highway Anchor/Doubleday 1998. The first novel by the famous Canadian playwright, it is in many ways a celebration of Cree culture, art and life, although I was completely wiped out by the books illumination of the harshest realities of the residential schooling era and the immense challenges thrown in the face of First nations peoples in Canada.

Reading this trio of books left me shaken to the core and filled with sadness for what this country has perpetrated in fearful pursuit of some kind of white, Christian ignoreland for the top half of the continent. I realized that the linking theme of exclusion harkened back to a book I’d read some years ago, A White Man’s Country Ted Ferguson – Doubleday, Toronto 1975, about the infamous Komagata Maru incident of 1914, in which 376 Punjabi refugees (all British subjects) were denied landing and left to starve on a steamer off Vancouver Harbour for 2 months before being sent back across the ocean.

I am a Canadian who is proud of the nation that has been built, and am in awe of heroics and determination that mark its past, but to look at only that is to not see reality. And to not know the stories outlined in the above books, and the many other stories of exclusion that continue to this day, is to ensure we walk blind into the next bout of fear mongering or race-based panic. Slowly, our country is growing up. The above authors are all integral and I believe heroic aspects of that maturing.

Lyrically, once again, my aim was to say as much as I could with the fewest words possible. The song is broken up quite literally one-book-per-verse. I realize it’s quite pretentious to pretend to encapsulate in three couplets the entire theme of a brilliant 400 page book, and I certainly don’t pretend that. These little songs are invitations, at best, to deeper study and deeper questions.

Verse One is the fleeing of Europe, only to be denied entry – a verse perhaps most inspired by the St Louis Incident (the St Louis was a ship bearing around 900 Jewish Refugees fleeing 1939 Germany. They were told at Halifax harbour that they would not make good settlers and were sent back to Europe where approx. 260 met their death in Nazi camps).

Verse Two takes place in Hastings Park, Vancouver, winter 1942, where thousands of Japanese Canadians were being held in inhumane conditions before being moved out to the desolate internment camps in the BC interior. A number of those evacuated were sent to forced labour on sugar beet farms in Alberta – an image and taste I contrast here with the thriving strawberry farms and canneries many of them owned and worked before being rounded up (farms, property and business holdings, I should note, that were never returned to them).

Verse Three could be a sidewalk on any major city in Canada, spots sometimes witness to the horrible toll the clash of cultures (and residential schooling) has had on some First Nations people. ‘shorn of...tongue, not allowed in the land it was made’ refers to the common residential school policy of severely punishing Native youth for speaking even one word of their own language – being beaten until they spoke one imported across the ocean, with no roots or connection to the land around them. Aggressive assimilationist policies like these were indeed designed to, in the words of one bureaucrat “kill the Indian in the child”.

The verse ends with a nod to the fourth book mentioned above.

Sonically, I wanted the verses to be subtly separated. The first has the rain pouring throughout (recorded out the window of my home studio the day I wrote the song). The second verse has no rain, and for the third I add a vocal percussion shuffle – which after the fact I realized reminded me of both a heartbeat and drum circle.

Although I was worried that the heaviness of this song would make it inappropriate in school concert settings, I’ve found to my surprise that In Performance Canada Doesn’t Need You consistently receives the strongest response from my High School audiences.

Activities & Lesson Ideas

Discussions

1.In the song lyrics, Mike Ford chooses to portray large events and themes in Canada's story using brief emblematic images (rather than spell out the themes in a more obvious or straightforward method). Why would he chose this approach?

2.What do you think the following lyric images refer to?

a.“…to escape from the boots to the boat…”

b.“Sour sugar beets, no strawberries today…”

c.“Footsteps ignore, step around on the ground…”

3.Each of the verses of ‘Canada Doesn’t Need You’ speak of an issue of exclusion in Canadian History (Refusal to admit Jewish refugees in the late 1930’s / Internment of Japanese Canadians during WW2 / Residential school oppression of First Nations youth).

a.What other events, large or small, in Canadian history appear to be cases of exclusion, restrictions of human rights?

b.Do such cases exist today? Could events such as those alluded to in “Canada Doesn’t Need You” occur in today’s society?

c.What events, images, policies etc. can you think of in today’s Canada display the opposite dynamic – an inclusive society?

Activities

1.Poetry: Mike Ford says that he was inspired by HAIKU poetry to create the verses of “Canada Doesn’t Need You” (although the form he uses in the song is not haiku). Haiku, a traditional poetic form from Japan, is characterized by very economical use of words – some haiku poets believe that a haiku poem should be said in one breath. English forms of haiku have developed differently than traditional Japanese forms, often being composed of 3 lines of 5/7/5 or perhaps 3/5/3 syllables, with a goal being the creation of a ‘multi-tiered painting, without telling all’, or the use of images for ‘showing’ as opposed to ‘telling’.

an aging willow

its image unsteady

in the flowing stream

faceless, just numbered

Lone pixel in the bitmap

I, anonymous

2.Project: Consider aspects of inclusion or exclusion. Create a Haiku focusing on a specific image that illustrates this theme. Perform or record your haiku, trying different rhythmic and/or melodic variations.

3.Contrast Collage: draw a line down the middle of a sheet of cardboard. Using found images (magazine cut-outs, drawings, product labels, etc) juxtapose two collage – one showing images you feel suggest societal inclusion, one showing images suggesting its opposite.

References & Suggested Readings

Truth & Reconciliation Commission

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada