In Winnipeg

Out in the sunshine evil dies.

- Edmund Vance Cook, 1917

Lyrics

IN WINNIPEG

words and music Mike Ford 2006

Are you tired - of your slaving

And getting older - and getting nothing

We’ve been working - in the factories

Inside the big machines - with fire and grease

But we won’t move a muscle - ‘til they negotiate

And give us something - And answer our pleas

WE DON’T WANNA FIGHT OR CAUSE A FRIGHT

OR BREAK THE SYSTEM OVER NIGHT

WE WON’T STAY ON OUR KNEES AND BEG

WE’RE STANDING TALL IN WINNIPEG

They’ve given the sack to - the regular police force

They’re bringing in the Specials - Special Police

Who are marching - with the Mounties 500 strong

With sawed-off yokes and baseball bats - to sweep us from the streets

WE DON’T WANNA FIGHT...

We work six-day weeks for pennies 2 holy days off, if any

Being slaves for banks and profiteers but it’s our hands that work the gears

So thank you - Committee of A Thousand

For thinking there’s a Bolshevik - under every pillow

And thank you - for rounding up the aliens

The undesirables – like my friend and me

WHO DON’T WANNA FIGHT OR CAUSE A FRIGHT

OR BREAK THE SYSTEM OVER NIGHT

WE WON’T STAY ON OUR KNEES AND BEG

WE’RE STANDING TALL IN WINNIPEG

STANDING TALL IN WINNIPEG

Key Terms & Phrases

Special police & regular police force

The ‘special police’ were essentially a mercenary force (that is, hired for a specific purpose) instated by the Winnipeg City Council to control and repress the striking workers and to maintain order in general. As told in the second stanza of In Winnipeg, these ‘specials’ replaced the regular police force, who had been disbanded by the City for their sympathy towards the Strike. (The local police union had in fact voted overwhelmingly in favour of striking, but the Central Strike Committee asked them to stay on the job to preserve order. This they did willingly, until they were replaced by the special police.) In the song Mike Ford also brings up the fact that the special police were armed with sawed-off yokes and baseball bats — unconventional weapons that demonstrated the City Council’s willingness to go to extremes in order to quell the strikers.

Mounties

The ‘Mounties’ (i.e. the Royal North-West Mounted Police, later the Royal Canadian Mounted Police [RCMP]) were brought in during the General Strike to quell the rioters. The Mounties are infamous for their actions on ‘Bloody Saturday‘ (June 21), when they attacked and fired into a crowd of strike supporters in downtown Winnipeg, killing two and injuring thirty. <<<After six weeks of stand-off that involved the arrest of strike leaders and union organizers, these strikers had gotten violent who had finally gotten violent and pushed over a streetcar and set it alight. >>>

Committee of A Thousand (Citizens Committee of 1000)

The Citizens Committee was an ad hoc group made up of manufacturers, bankers, and politicians that led the opposition to the strike. Wealthy and influential, they had Ottawa’s ear, and very soon its backing as well. The Central Strike Committee, not surprisingly, did not even receive an audience. (The government’s concern was not without reason; sympathy strikes had begun to appear across the nation, and revolution seemed to be in the air. The Russian Revolution in 1917 only heightened the paranoia.) Backed by the federal and provincial governments, the Citizen’s Committee called for the mass arrest of strike organizers as well as a new ‘special police corps’ to carry it out. There was only one problem: legally, the arrests could not be carried out. Unhindered, the Citizens Committee convinced Ottawa to amend Canada’s Immigration Act and Criminal Code to allow the arrest, detention, and deportation of naturalized citizens on the mere suspicion of advocating revolution.

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, founded by Vladimir Lenin, were an organization of professional revolutionaries, who considered themselves as the vanguard of the revolutionary working class of Russia. Their beliefs and practices were often referred to as Bolshevism. Although the Bolsheviks were not monolithic, they were characterized by a rigid adherence to the leadership of the central committee, based on the principles of democratic centralism. 1n 1952, the official name of the state political party of The Soviet Union was changed for ‘Bolshevik’ to ‘Communist’. In many countries around the world, and certainly in Winnipeg of 1919, the term ‘Bolshevik’ was used to accuse those who were feared to be agitating for a Soviet-style workers revolution, or who were indeed feared to be taking orders from revolutionary leaders in Moscow.

Aliens

The term ‘enemy alien’ has been used in Canada and other countries during wartime to describe settlers who have immigrated from ‘enemy’ countries. Identification of and treatment of those termed ‘enemy aliens’ has varied through history. During WW1, for instance, immigrants from The Ukraine were made to ‘register’ as enemy aliens, and several thousand were interned in, while during WW2, almost every single Canadian of Japanese heritage (immigrant or not) was interned. With WW1 having ended only six months earlier, and amid worries of global revolution, the exclusionary (and arguably racist and paranoid) concept of ‘the enemy alien’ was front and centre for many authorities during the Winnipeg General Strike. In the aftermath of the strike, Canada’s parliament in Ottawa enacted…

Profiteers

The term profiteer refers to someone who makes what is considered an unreasonable profit especially on the sale of essential goods during times of emergency. The term 'war profiteer' evokes two stereotypes in popular culture: the rich businessman who sells weapons to governments, and the semi-criminal who sells (rationed) goods to ordinary citizens on the ‘black market’. It’s been said that one of the causes of mounting anger that led to the Winnipeg General Strike was the massive war-profiteering on the part of wealthy Winnipeg capitalists (i.e. – using the urgency of the war to make fortunes in arms and supply profits, while the average worker risked his life in the carnage overseas.

Historical Context

The Winnipeg General Strike (May 15 to June 29, 1919) is a fascinating episode in Canadian history, one that may surprise those who perceive Canada’s history as bereft of any excitement or radicalism outside the World Wars. In fact, the story of Canada’s labour movement is one filled with drama, action and violence. Among developed nations, for instance, Canada is second only to the United States in violence related to strikes and strike-breaking.

The Winnipeg General Strike easily qualifies as the peak of labour unrest in Canada, at least in terms of the sheer number of people involved, the level of organisation and radicalism of the strike leaders, and the scale of response from Ottawa. By 1919 Winnipeg was the third largest city in Canada, and the battle for workers’ rights had already achieved some important victories. As one of the most unionized cities in the nation, Winnipeg was also one of the more radical, inspired not least by the recent events in Russia (1917-18) that saw Lenin’s Bolshevik party come to power under the banner of working-class solidarity. In the Manitoba capital the storm was near-perfect; by Spring 1919 there was enough chaos and disgruntlement and radicalism - in short, “labour unrest” - that the balance finally tipped.

Causes

makes what is considered an unreasonable profit especially on the sale of essential goods during times of emergency. The term 'war profiteer' evokes two stereotypes in popular culture: the rich businessman who sells weapons to governments, and the semi-criminal who sells (rationed) goods to ordinary citizens on the ‘black market’. It’s been said that one of the causes of mounting anger that led to the Winnipeg General Strike was the massive war-profiteering on the part of wealthy Winnipeg capitalists (i.e. – using the urgency of the war to make fortunes in arms and supply profits, while the average worker risked his life in the carnage overseas.

Elements leading up to that ‘breaking storm’ included:

- Full employment of war years is over

- Zero social safety net

- Returning soldiers seeking normalcy that doesn’t exist

- Growing societal gap – some employers made huge fortunes during the war, while thousands without privilege were killed or maimed overseas

- Post-war economic downturn

- Unease among some regarding north Winnipeg’s immigrant communities, combined with fears of revolution spreading from Russia.

- Business leaders ignoring workers’ pleas for a living wage and right to organize.

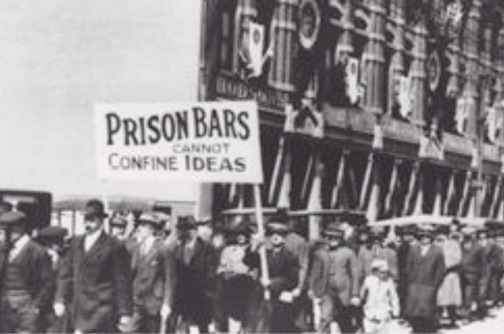

A general strike was called, and on May 15, 1919, at precisely 11:00 a.m. more than 30,000 workers left their jobs in solidarity, bringing the city of Winnipeg to a virtual standstill. The strike proceeds peacefully for weeks.

Demands

- Living Wage

- 8-hour day

- The right to organize

Police, even though they are still at work (by order of strike committee) are all fired for supporting their union. ‘Specials’ are hired (at $6 a day!) given armbands and truncheons (including improvised ones like wagon spokes and sawed-off yokes. The city goes through an oppressive heatwave and damaging thunderstorms.

The Royal North-West Mounted Police arrest strike leaders and confiscate subscription lists of the workers’ paper. Strike leaders are put on trial by the Comittee of 1000.

Bloody Sunday

On June 21st, veterans stage silent march in support of the strike. Mayor orders them to disperse. They refuse. City sends in a streetcar (a huge anti-strike symbol-streetcar drivers were among the most militant of the strike supporters). Mounties charge the crowd several times, finally firing guns. One bystander (or rock thrower) is shot through the heart. Panicked crowds are cornered and ‘Specials’ wade in and beat them. The Military rolls in to occupy the main streets. It becomes known as Bloody Saturday. Once again, the city is silent – for much different reasons.

Through all this, thousands of immigrants involved in the strike, many of whom were beaten, were terrified to give their names for fear of deportation. The killed striker, Mike Sicolowski, is buried in a nameless grave – his wife and children do not even attend the burial, for fear of deportation. In the days following, strikers are fired ‘enthusiastically’ by many trades, the post office, etc.

Composer Notes

I’m fascinated by stories of The Winnipeg general Strike of 1919. The more I learn of it, the more I feel it is an important event in not only Canadian, but world history. Many dynamics of this 6-week shutdown of an entire city are relevant to the quest for labour rights everywhere. The aspirations and demands of the strikers are testament to the trans-national nature of the labour movements of that era – movements inspired by ideas spread from country to country, language to language, through visual art, poetry and song. Also, aspects of popular, elite and government responses to the 1919 strike are textbook examples of xenophobia and fear-mongering that we would be well to learn from today.

Lyrically, I’ve written my song from a specific point of view – perhaps one held by the majority of strikers, perhaps not – that of the frustrated labourer feeling the solidarity of the crowd, demanding change, but not by any means necessary. The song could have been as effectively written from other points of view – for instance that of a Winnipeg political or industrial leader, or member of The Committee of 1000, or, alternatively, that of a frustrated striker espousing a less restrained, less peaceful way forward. (I often suggest this as a writing exercise for students).

The song’s narrator is at once making a crowd-rallying speech as he is describing the unfolding scene for the listener. It occurs to me that as that era had much less in the way of electronic media and amplification, more orators would be needed than is the case today. Where now one talented speaker can be heard by crowds of unlimited size, in 1919 perhaps a whole collection of orators would be needed to pass on the latest strike council news, orders and rallying points.

Each verse has a specific purpose. The 1st briefly lays out the overall scenario, the 2nd describes a few images showing authorities’ heavy-handed reactions, and the 3rd points sarcastically to the racist undertones of the authorities’ response. In each case I plant a simple blunt image to aid the point – the fire and grease of the work machines, the sawed off yokes carried by special police (the most startling discovery I made in my research, and an image that also reminds of the agricultural dynamic of the time and place), and the every pillow the narrator accuses the over-zealous Bolshevik-hunters of looking under.

Musically, I wanted the piece to have a driving pop-rock feel (somewhere between Beatles and Green Day) with a sing-a-long chorus appropriate to the solidarity message. It’s fun to imagine the different ways the song might sound voicing the different points of view suggested above (how about techno-robotic for the authority voice, punk-screamo for the unbridled rebel voice ?). For the recording, we created a faux rally speaker with blow-horn for the intro, to help create the story’s time and place. We fooled around with the feedback and found the results evoked a kind of factory site in the background – a classic example of some random experimentation enriching a piece. We also had fun folding the fire bell sound effect into the subsequent guitar line. I felt it important as well to bring in a guest voice after the line ‘like my friend and me’, in this case my Moxy Früvous colleague, CBC host Jian Ghomeshi (which, with fellow Früv’s Murray Foster on Bass and David Matheson on Piano makes the song a rare full-band reunion!).

Activities & Lesson Ideas

Class Discussion Questions

1. The lead-ups to the Strike, and to Bloody Sunday, are often described as a ‘Perfect Storm’ or ‘Powder Keg’ a combination of problems and factors that appear to inevitably lead to an explosive event. Are there elements in today’s society could be described as being ingredients for a Perfect Storm or Powder Keg? If so, what are they? What kind of explosive events could result? What measures can be suggested to avoid such a scenario?

2. What conditions today is a powderkeg? What could blow? What techniques could be used ?

3. Clearly, one of the strike’s causes was the lot returning soldiers were left with. Risking life for democracy in the hell of ww1 across the ocean, the majority of them returned to unemployment, meagre government assistance, and rising costs. (eye-witness quote). How have returning soldiers been treated in other eras? Today?

4. In the early days of the strike, the mayor issued a ban on public demonstrations. We are told that today we have freedom of assembly – but are there instances where this is not so? What would reasons for such a ban be? Then, as well as today?

5. What hardships might a family encounter during a strike?

Activities / Projects

Song-writing A

Using the melody and music of Ford’s In Winnipeg, have groups of students assume different viewpoints and actors in the General Strike and write new lyrics from that perspective. For example, one group can write from the perspective of the Committee of A Thousand; another from pro-strike veterans; another from anti-strike veterans; another from the viewpoint of the Federal Government, and so on.

Song-writing B

Bring in a copy of the labour movement anthem Solidarity Forever along with the lyrics (see Resources). Analyze the words to the song as a class and then sing it together. Next, in groups of 4-5 have the students write a verse of their own and ask them to perform it at the end of class. Solidarity Forever was put to the tune of When the Saints Go Marching In and is thus simple, catchy and rousing. If the

teacher or one of the students plays guitar or another accessible instrument and can accompany the singing, the activity will be all the more memorable and effective.

References & Suggested Readings

1919: The Winnipeg General Strike - A Blog

Don’t let the “blog” part fool you: this is actually a great resource with a treasure-trove of easily accessible information on most every aspect of the Winnipeg General Strike. In addition to a day-by-day run-through of the strike, the site also includes a section for “Context and Reference” (including the Russian Revolution, the State of Labour in Canada, and the city of Winnipeg in 1918-19) as well as a set of bios for key figures on each side (the “Strikers’ Side” and the “Government Side”), among other things. There is also a page of reference links for more resources and information.

CBC Digital Archives: Remembering the Winnipeg General Strike

The CBC Digital Archives cover a large number of subjects and events and are an excellent resource for teachers who want to include primary source material in their lessons and assignments. This particular page about the Winnipeg General Strike provides the audio of a CBC Radio broadcast from the program ‘Between Ourselves,’ originally broadcast on May 15th, 1969. The page also provides an overview of the Strike, complete with context, key players and key events.

Strike! The Musical by Dan Shur

A brilliant Musical by Winnipeg composer Dan Shur. The web site takes you to great info about the Musical – youtube clips, iTunes links, synopsis, photos, reviews

Bumstead, J.M The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 – An Illustrated History Watson Dwyer, Winnipeg 1994

The following poem, by Canadian Poet Edmund Vance Cook, written in 1917, expresses a viewpoint perhaps similar to one held by striking workers and espoused by strike leaders who saw the larger ramifications of the authorities’ backlash to the Winnipeg workers of 1919:

Sedition

By Edmund Vance Cook, 1917

You cannot salt the eagle's tail

Nor limit thought's dominion

You cannot put ideas in jail

You can't deport opinion

If any cause be dross and lies

Then drag it to the light

Out in the sunshine evil dies

But fattens on the night

You cannot make a truth untrue

By dint of legal fiction

You cannot imprison human view

You can't convict conviction

For though by thumbscrew and by rack

By exile and by prison

Truth has been crushed and palled and black

The truth has always risen

You cannot quell a vicious thought

Except that thought be free

Gag it, and you'll find it taught

On every land and sea

Truth asks no favor for her blade

Upon the field with error

Nor are her converts ever made

By threat of force and terror

You cannot salt the eagle's tail

Nor limit thought's dominion

You cannot put ideas in jail

You can't deport opinion